Victorian London – confident and thriving

During the first half of the 19th century, London was the world’s largest port and wealthiest city. The Great Exhibition of 1851 provided a showcase to the world of Britain’s prowess in science and technology, invention, engineering, manufacturing and culture. The Crystal Palace, the central icon of the exhibition, reflected the confidence and dynamism of the period and made a powerful statement that Britain and London were open for business.

By 1800, congestion on the river had become so extreme that it limited the ability of the port to expand. This led to a massive off-river dock building programme. The new docks provided the ability for ships to unload directly into purpose-built warehouses, giving the port a quantum leap in capacity.

London’s traffic problems

In 1801 the population of London had been 1.1 million. By 1860 it had risen to 3.2 million, one third of whom lived to the East of London Bridge. Streets near the bridge approaches were gridlocked with horse-drawn vehicles of all descriptions, including omnibuses. The problem was largely caused by the success of the new docks. Goods could now be landed easily, but transporting them by road to the railway termini was a huge challenge. A new bridge, downstream from London Bridge was urgently needed.

In August 1882, traffic across London Bridge was observed over a two-day period. The average daily traffic was 22,242 vehicles and 110,525 pedestrians.

The bodies responsible for London bridges

For centuries, bridges in the City of London had been the remit of the Bridge House Estates Trust of the City of London Corporation, administered by the Bridge House Estates Committee (BHEC). The Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW) was created by the Metropolis Local Management Act of 1855 to regulate the construction of buildings in London and to provide the improvements in infrastructure required to cope with London’s rapid growth. So now there were two bodies with responsibility for bridges. They did not always see eye to eye.

Demand grows for a new river crossing east of London Bridge

In 1874, the Court of Common Council instructed BHEC to make recommendations on the best way to increase the capacity of London Bridge. In December 1875, the Committee reported, recommending that London Bridge be widened, but pressure was growing from business houses, merchants and traders for an entirely new crossing East of the Tower of London. In January 1876, the Court instructed BHEC to consider the relative advantages and costs of a new bridge or subway at this location. A new committee was formed – the Special Bridge or Subway Committee (SBSC).

From the ridiculous to the sublime – proposals considered by the Special Bridge or Subway Committee, June 1876 – December 1878

The Special Bridge or Subway Committee was not well equipped to evaluate competing bridge designs and make a recommendation. The committee included elected members and professional men, but they were not engineers. Neither were they experienced in contracting or project management.

Although they did ask the Court of Common Council for permission to advertise for bridge designs, this permission was not forthcoming. However, it seems that news of the committee’s work spread around the civil engineering community and letters from budding bridge designers to the committee, or to the Lord Mayor, would result in an invitation for the sender to attend a meeting of the committee to present their design.

Proposals presented to the committee included:

- A proposal by John Keith for a cast iron arch subway or “sub-riverian arcade”.

- A proposal by George Barclay Bruce for a transporter bridge.

- A proposal by inventor Frederic Barnett for a duplex bridge. This was a double swing bridge designed to allow shipping and vehicular traffic to pass unimpeded at all times.

- A proposal by Edward Perrett for a high-level bridge, with hydraulic hoists at each end.

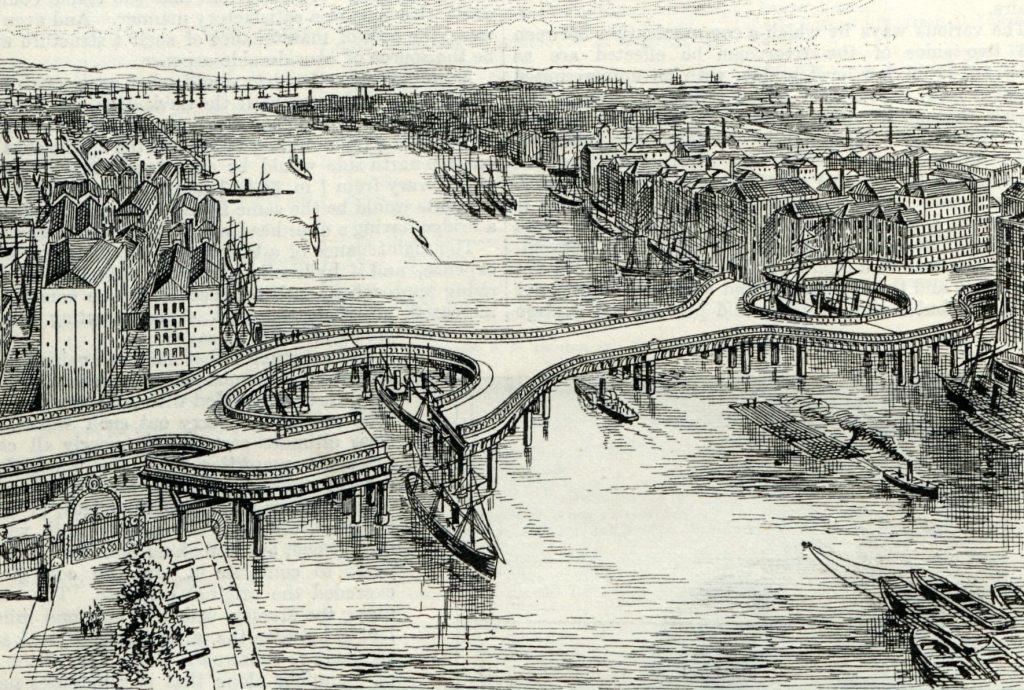

- A proposal by Thomas Claxton Fidler for a high-level bridge featuring a hydraulic lift at one end and a spiral at the other.

- A proposal by Sidengham Duer for a high-level bridge with a hydraulically-operated platform at each end.

- A proposal by John P Drake for a swing bridge.

- A proposal by C T Guthrie for a transporter Bridge or “River Railway Line”. This featured a level track on the bed of the river on which a self-propelled platform would shuttle between the Middlesex and Surrey banks.

The committee turned to City Architect, Horace Jones, who was requested to prepare an evaluation of the proposals submitted so far. This he did. Further proposals kept coming, including:

- A proposal by Percy Westmacott for a hydraulic swing bridge.

- A proposal by G L Shand, also for a swing bridge.

- A proposal by C Piehliere for a low-level bridge with a central lifting span.

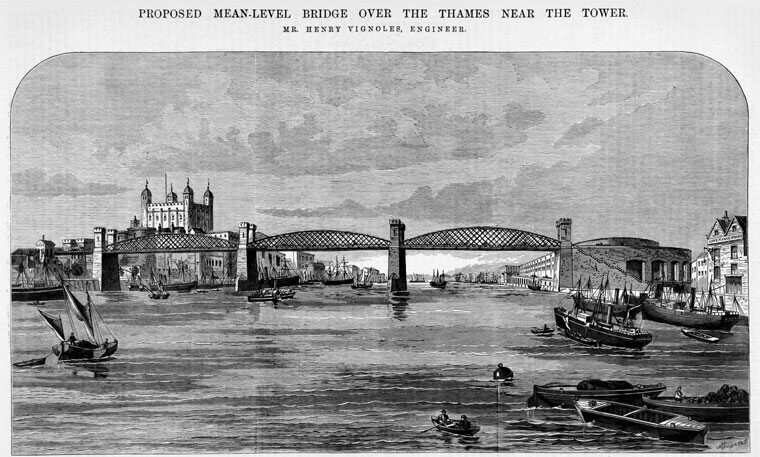

- A proposal by Henry Vignoles for a three span high-level bridge.

At the meeting on 3 May, 1877, a report to the Court of Common Council was signed. The Special Bridge or Subway Committee concluded that,

“Having very fully and carefully considered this very important question, both with regard to the imperative necessity for the relief of the traffic of this City, and the convenience of the river navigation, we are of the opinion that the best means to be adopted, in order to meet the wants of, and to relieve generally the continuously increasing traffic of this City, will be to construct at the site indicated in our former report, viz., that approached from Little Tower Hill and Irongate Stairs on the north side, and from Horselydown Lane and Stairs on the south side of the river, a low-level bridge, with proper arrangements for affording the requisite facilities for passage of vessels up and down the river Thames.”

This report was accepted by the Court of Common Council. It would seem that some progress had been made. It would be a bridge and not a subway!

Still more designers pitched proposals, including:

- A proposal by George Rennie for a hydraulically-powered swing.

- A proposal by Francis Ingram Palmer for a double duplex bridge with four moving platforms aimed at achieving uninterrupted river and bridge traffic.

The Metropolitan Board of Works weighs in

Having finally a little time to devote to other projects, Sir Joseph Bazalgette turned his attention to the matter of the “Tower Bridge”. He recommended that it should be made of steel and should be a high-level bridge, concluding that:

“if masted vessels which have topmasts exceeding 65 feet above the water level, being one fourth of the total number, would lower their top masts, a high-level bridge might be constructed which should give a clear headway for all ships to pass under it, and which might be provided with convenient approaches and gradients.”

A clash of Titans

Following the receipt by the MBW of a letter from the Comptroller of Bridge House Estates Trust, the Special Bridge or Subway Committee met with the Works and General Purposes Committee of the MBW on 26 November, 1877. The purpose of the meeting was to determine whether there was scope for the City and the MBW to collaborate on the bridge project. After the meeting, the MBW committee resolved that,

“the further consideration of the subject [of the bridge] be adjourned until the [Board’s] Engineer has conferred with the City Architect and inspected the plans prepared by him, and has reported to the Committee upon such plans, and also generally his own views upon the subject.”

The meeting between Sir Joseph and Horace Jones took place on 5 December, 1877. Both men left the meeting with the distinct impression that the other was not really interested in any kind of collaboration. Sir Joseph set about the completion of the only part of his brief that he could fulfil – that of presenting his own views on the subject of the new bridge. A great man, who made things happen, Sir Joseph already had three alternative designs for a high-level bridge on his drawing board. The bridge was to have a clear headway of 65 feet above Trinity high water and a width of 60 feet.

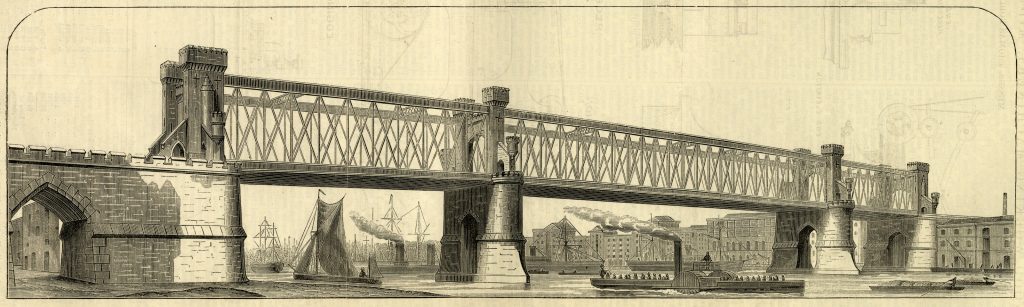

His first and simplest design was for a bridge of three simply-supported steel lattice girder spans, resting on two piers in the river to provide a central channel of 444 feet and two side channels of 184 feet. The spacing of the piers took into consideration the tiers of ships maintained on the Middlesex and Surrey banks at that time. The girders were some 50 feet tall, giving the bridge a workmanlike but austere appearance. There is no doubt that this was a practical design, but it was not a pretty one.

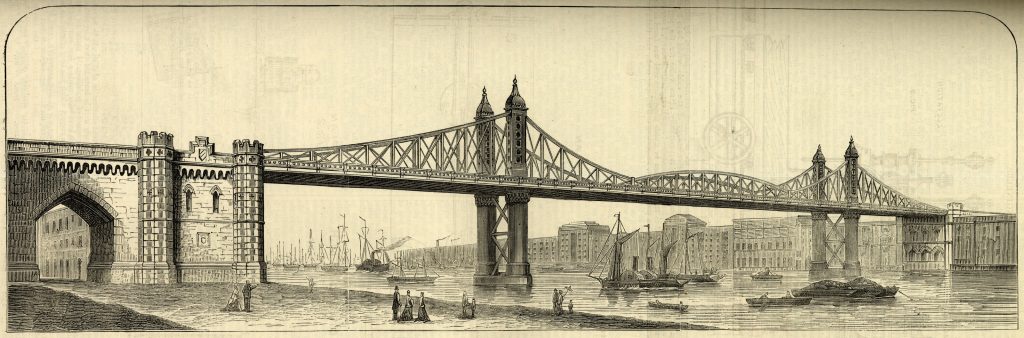

The second design provided the same channels for shipping as the first solution but presented a more pleasing appearance. Each pier supported steel lattice cantilever sections. The shoreward sections were firmly secured to the bridge abutments, while the sections carrying the roadway towards the centre of the river carried a simply-supported arched steel lattice girder. The whole is very reminiscent of the Firth of Forth Rail Bridge (but on a much smaller scale) on which construction would commence in 1882.

The third Bazalgette design was for a very elegant single-span braced-arch bridge crossing the river in one span of 850 feet, with the arch having a rise of one eighth of the span. Its appearance was not unlike the much later Tyne Bridge.

In his report, dated 22 March, 1878, Sir Joseph described his third design only. He described the easy gradients, stressed the advantages to be enjoyed by vehicular traffic and foot-passengers, and set out the reasons why his proposed design was to be preferred.

Sir Joseph submitted his proposals to the MBW Board without seeking the approval of the City Architect. There is no doubt that this was regarded as a snub by Horace Jones and the Corporation. MBW initiated the preparation of a Parliamentary Bill to build the high-level bridge. This was the second MBW initiative to be successfully opposed by the Corporation and the Thames Conservancy Board due to the restricted headway of the bridge.

In October 1878, Horace Jones released a report commenting on Bazalgette’s designs. His view was that a high-level bridge of the headway proposed disregarded the evidence, views, wishes and interests of the wharf owners and ship owners trading between the proposed bridge and London Bridge.

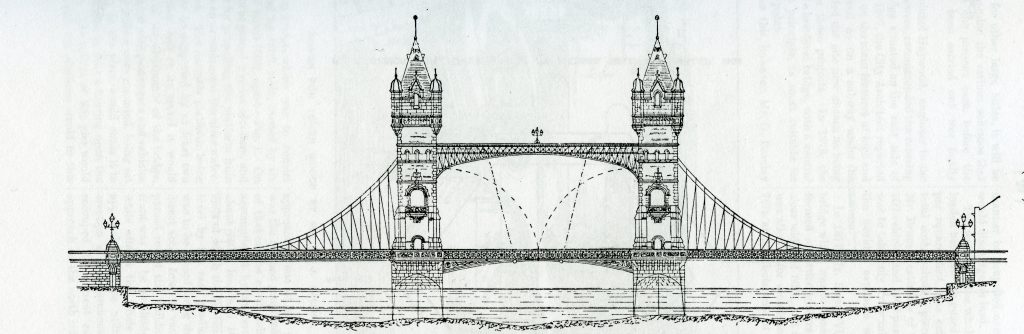

Horace Jones’ initial specification and outline design

Jones devoted the last quarter of his report to setting out and promoting his own proposals for the bridge. It should be a low-level bascule bridge which, when closed, should offer the same headway above Trinity high water level as London Bridge. The approaches would have easy gradients, minimising the amount of land which would have to be purchased. The centre opening would be 300 feet, much wider than that possible with a swing bridge and there would be less obstruction to navigation, only two piers being required. The central span would comprise two hinged steel platforms, each lifted by eight chains passing over rotating barrels mounted in the arches to winding machinery in the towers. A headway of 100 feet would be provided over a channel width of 150 feet. The side spans could be simply-supported or supported by suspension chains. The architecture would blend with that of the Tower of London. His proposal is clearly the original inspiration for Tower Bridge as built, even if the towers have something of the fairy-tale castle about them.

After this promising start, it would seem that no concrete steps were taken to progress the project. The Special Bridge or Subway Committee was dissolved in January 1879, steering of the project reverting to the Bridge House Estates Committee. But pressure from the public and businesses for the new crossing continued to build.

The impact of the Tay Bridge disaster

On Sunday 28 December, 1879, shortly after seven o’clock in the evening and in extremely high winds, a large portion of the Tay Bridge fell into the water below. A train was on the bridge at the time and was precipitated into the stream. There were about eighty people on the train, all of whom lost their lives. This incident sent shock waves through both the Victorian engineering profession and the general public. All thoughts of bridge building were set aside pending the report of an enquiry. The report of 30 June, 1880, concluded:

“The fall of the bridge was occasioned by the insufficiency of the cross bracing and its fastenings to sustain the force of the gale.”

The designer, Sir Thomas Bouch, had used a wind pressure of 10 pounds per square foot in his calculations. The disaster spelled the end of Bouch’s career and he was replaced as engineer on the Forth Bridge in January, 1881.

A committee was established by the Board of Trade, comprising eminent engineers of the day, to set out five rules to be applied by bridge designers when performing wind loading calculations. For railway bridges and viaducts, a maximum wind pressure of 56 pounds per square foot was to be used. This was the figure which would be applied for the new Tower Bridge when it came to be designed a few years later.

The last throw of the dice for Sir Joseph Bazalgette

In 1882, no doubt frustrated by the continued lack of progress on the project, Sir Joseph Bazalgette submitted a revised proposal for his braced arch high-level bridge, increasing the headway from 65 to 85 feet above Trinity high water level and improving the Southern approaches. He also submitted proposals for low level bridges (with and without provision for opening) and a tunnel.

Two private Bills were introduced in early 1883, one for a duplex bridge and one for a subway – both private ventures seeking to earn revenue from tolls. These were successfully opposed by the Corporation.

1884 – decision time!

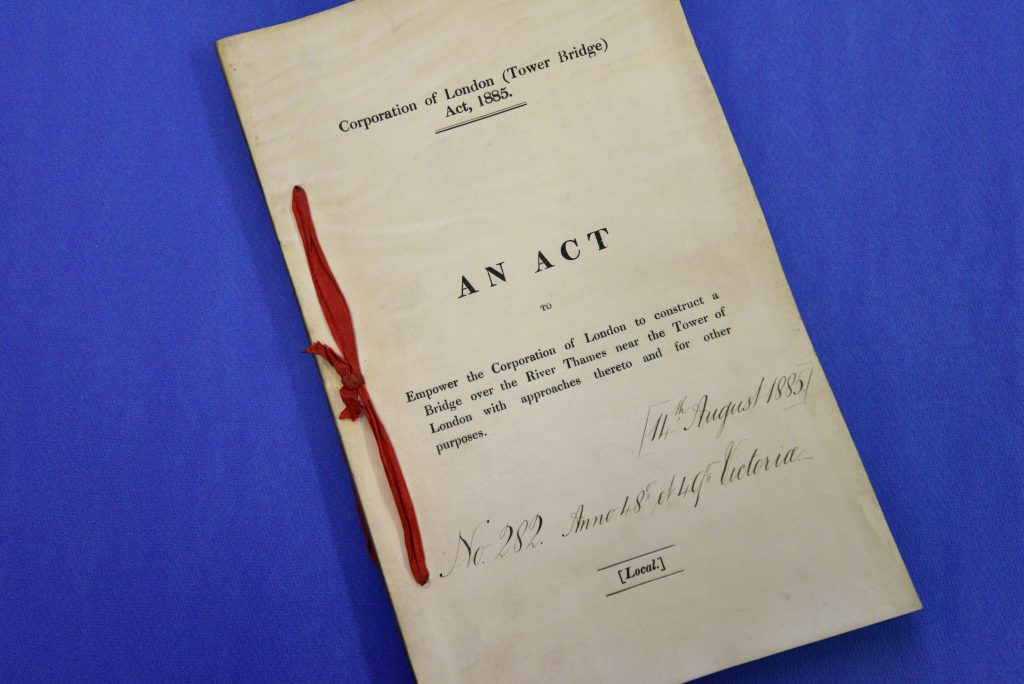

On 24 July, 1884, the BHEC reported that the Corporation should construct an opening low-level bridge, funded by Bridge House Estates. The Committee also offered to firm up the design and cost estimates with a view to an application being made to Parliament later in the year.

On 29 October, 1884, BHEC presented a report to the Court of Common Council detailing the results of inspections made of low-level opening bridges in Great Britain and the Continent. The report contained sketches by Horace Jones of swing bridge and bascule bridge variants of the new Tower Bridge. Jones had also consulted John Wolfe Barry and a letter from Barry was appended to the Committee’s report, endorsing the practicability of the outline designs. Barry is believed to have spent a period of five weeks on this consultation, during which he prepared a cost estimate of £750,000 to build the bridge, which included the cost of land to be purchased to enable the project.

The Court of Common Council unanimously adopted the bascule bridge proposal. A Bill was prepared and considered by the House in the Spring of 1885. There was some push-back on the proposal from the engineering press. The Engineer of November 7 contained an editorial summarising the progress of the mooted bridge from 1866 to the present time, but expressed concerns as to whether Horace Jones was the right man for the job:

“With every respect for Mr. Horace Jones, the genial and popular City architect, we are bound to say that he is hardly the man to design the bridge, although he may protect the interests of the Corporation in determining on a design. If we may be allowed to say so, there is too much architecture and too little engineering in his scheme.”

Unsolicited designs kept coming in, but the die was cast. The Bill received its third reading in July despite strong opposition from wharf owners of the Upper Pool. Royal Assent was received on 14th August and in September the Court of Common Council authorised the BHEC to build the bridge. Horace Jones was appointed architect and John Wolfe Barry engineer.

The detailed design phase

From the summer of 1885, Barry worked on the design with little input from Jones as the bridge was effectively a steel bridge with a stone facade. Barry had been in practice with Henry Marc Brunel (son of Isambard Kingdom Brunel) since 1878, and Brunel was given responsibility for much of the detailed design work and its attendant calculations. George Daniel Stevenson took responsibility for the detailed architectural design of the external masonry. Design and drawing work would occupy this team for the next four years.

Tenders for Contract No. 1 (piers and abutments) were delivered before noon on Monday 29 March, 1886, so by that date Barry must have prepared at least an outline design of the whole bridge, sufficient to produce a close estimate of the total weight the foundations were required to bear, plus a detailed design and specification for the piers and abutments.

Work began without delay in April 1886, and a memorial stone was laid by H. R. H. the Prince of Wales on 21 June 1886, with music supplied by the Band of the Coldstream Guards. Detailed design work on the superstructure and machinery of the bridge was ongoing throughout 1886, 1887 and 1888.

It is extraordinary that a bridge of such magnitude and complexity could be designed by such a small team, using drawing boards, slide rules and trigonometrical tables, and with no access to electronic calculators, spreadsheets, Computer Aided Design packages, 3D finite element analysis software, copiers or printers.